For fiscal year 2000, Yale’s endowment fund produced a 701% internal rate of return (IRR). While looking only at IRR has limitations (or so we are told), the point is, times were good. Sure, Yale has access to private investment opportunities. But from 1995 to 2000, the public stock market doubled. Twice. Times were indeed good.

From time to time I think about the dot-com era. For those in their 30s, the dot-com era is both a very real part of our lives but also something before our time. It’s mystified and mocked simultaneously.

I should mention something; I started writing a large portion of this 𝚖̶𝚊̶𝚗̶𝚒̶𝚏̶𝚎̶𝚜̶𝚝̶𝚘̶ a couple of years ago for a different purpose. I ultimately put the proverbial pen down. Now feels like an interesting time to revisit it. And to revisit, well, everything.

In the years leading up to 2000, many of the more speculative high-tech stocks provided returns that made even a 300% return look pedestrian. For this reason, seemingly everyone thought they could be a “day trader” and many took the plunge. Twenty- and thirty-somethings were literally packing up their respective desks at their well-paying corporate jobs to take part in the modern gold rush.

I am now writing this in a time when we are seeing largely unprecedented volatility in the public stock market due to the COVID-19 virus. In March of this year, approximately 20 years after to dot-com boom and bust, most Americans once again packed up their desks. This time around the circumstances are different, but the lessons of the past may be worth considering.

Timing Is 𝙴̶𝚟̶𝚎̶𝚛̶𝚢̶𝚝̶𝚑̶𝚒̶𝚗̶𝚐̶ Important

During the boom, there were a litany of great entrepreneurs that took action and created enduring companies from nothing. There were also legendary failures.

Pets.com is looked at as one of those failures. In fact, if you lived through it or are even moderately well-read on the dot-com bust, then you know Pets.com. It’s referenced constantly as the biggest dot-com era failure. There’s even a Super Bowl ad with a sock puppet, because of course there is.

Looking a little deeper at some lesser known dot-com era start-ups better illuminates the dynamics of that era.

In a November 1999 initial public offering (IPO), something called Webvan raised $375 million. The company was valued at $1.2 billion. The average American has never heard of this particular company. Before you Google it; Webvan was an online grocery delivery service. Yes, in 1999! It was, ultimately, ahead of its time. Like, way ahead of its time. Unsurprisingly, that lead to its demise. The timing was not right.

Also in 1999, Kozmo.com raised a quarter of a billion dollars. Let me write that out numerically to dramatize it — $250,000,000. Kozmo was offering same day delivery of amenities like DVDs, CDs, books, food, and other consumer packaged goods. In March of 2000, Kozmo filed with the Securities & Exchange Commission for its IPO. By August of that same year, it was forced to withdraw the IPO. For some current context — Etsy raised $267M in venture capital at the time it’s 2015 IPO. Unlike for Etsy, the timing was not right for Kozmo.

In 2020, major companies are still trying to get same day (including grocery) delivery right. Kozmo and Webvan, the scrappy start-ups, wanted to tackle that immense logistics challenge two decades ago.

One of Komo’s investors in 1999 was Amazon.com—and interesting but not terribly surprising fact. Now for what should blow your mind (or at least come as a surprise). The money behind Webvan? That was Borders. Yes, that Borders Books & Music — the one-time could have been Amazon competitor.

Time Over Timing

Even for a large, well-funded corporation, if it cannot afford to keep the operation running, there is no chance to win. Pets.com, Kozmo, Webvan, and even Borders all failed to sustain for a long enough period to be able to iterate and to scale. Time over timing.

For the retail investor that is relatively young, the best play in the playbook is to use the one thing we have to our advantage while we have it — a plethora of time. Retail investors needn’t be concerned with quarterly earnings, investor redemptions, or other short-term factors.

So we’ve got that going for us… which is nice.

Jeff Bezos, maybe more than any other major company CEO, has taken a similar long-term stance. Amazon might be the ultimate example of playing the long game. For Bezos, the sale of books and common household items created powerful cash flows and funded Amazon’s investments, i.e., the entrance to all other businesses such as original content, grocery, AmazonBrand products, and even its expansive delivery network. All of it.

If we — the average retail investor — are lucky enough to have “disposable income” (meaning simply positive cash flows where income is greater than expenses), that is our version of revenues from books, paper towels, and hand soap.

The important thing is to have a strategy to put that income to work over the long-term.

Keep It Simple

First, the goal of the common investor, like you or I, should be simple. How about this… simply having the ability to retire. That’s a worthy goal summed up in a short and simple statement. But that does not make it easily executed.

In a world in which retirement income is largely reliant on individual 401(k) and IRA accounts, there’s a reason why it is hard for the average retail investor to keep a clear mind in the face of the type of adversity we are living through in 2020.

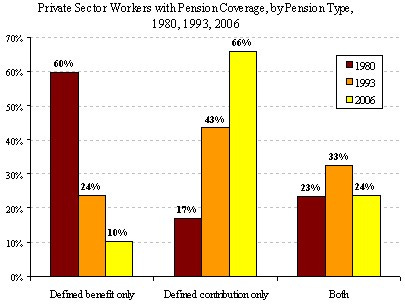

Unlike today, in 1980 over 80% of private sector workers had a pension. As of 2018, that percentage dropped well under 20%. This leads to much more pressure on us as individuals compared to decades prior.

No one investment decision is likely to be make or break in the long term. If it is, then that was the wrong strategy to start. With all the pressure falling on us as individuals, it is wise to have a strategy for the long-view.

COVID-19 has quite literally stopped the economy in its tracks. With equities, fixed income vehicles, and commodities all experiencing unprecedented volatility, now could be a time to take the governor off our proverbial investment engines. However, that opportunity must be approached with balance as the goal is not to gamble or take undue risks.

I did say earlier that now may be a time to “revisit everything.” But, after searching your investment soul, there is a simple way to summarize one’s outlook. At the highest level, either we choose to be long capitalism or we choose to be short capitalism. The d̶e̶v̶i̶l̶ fun is in the details.

These are five principles I’m using to maintain a holistic view in trying times:

STATE YOUR GOAL

TAKE RESPONSIBILITY

DO NOT PANIC

STAY IN THE GAME

TAKE THE LONG-VIEW

EDITORS NOTE: This was simply written as a reminder to not forget the principles listed above even in difficult times. Oh, and to close out that Pets.com anecdote — In the spring of last year, something called Chewy.com was finishing up its IPO roadshow. That’s where the company, an online pet food delivery service, and its investment bankers sell other institutional investors on the value of its stock. This past June, Chewy raised $1 billion from the stock sale and now trades on the New York Stock Exchange under the ticker symbol CHWY. As of press date, CHWY has a market capitalization of nearly $20B. Somwhere there’s a sock puppet ̶l̶a̶u̶g̶h̶i̶n̶g̶ ̶ crying.